Knowing what we know

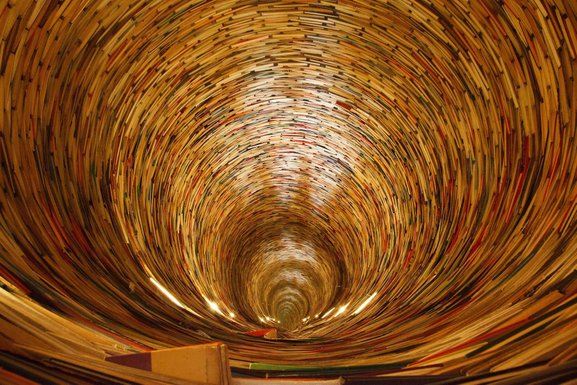

THE SCULPTING OF KNOWLEDGE :

Carving until we reach a scientifically sound model

Imagine being a sculptor. Starting with nothing - or rather everything - and then begin to strip away everything that doesn't feel like it belongs in the picture. Initially, there is no shape, no model and not even a clear vision of where this is going. But for each stroke, the uncertainty is reduced, and a sketch starts to emerge. For each stroke there is less noise, and a previously hidden structure starts to appear. Each cut represents a decision about what belongs and what has to be discarded.

In many ways, this resembles the process of carving out scientific knowledge. In the beginning, every statement and every input is a potential fact. But if any two informations are contradicting each other, we need to throw away at least one of them. And at that point in time, the scientist sculptor is confronted with a very difficult challenge. Because how will you be able to tell which information is a falsehood, and which information is true.

It turns out that the word “true” has a very distinct, and far from glorifying meaning.

That a sentence is considered possibly true, simply means “not contradicting any of the stuff that we have already labeled true”. And it can be taken a notch up the “truth scale”, if the statement at the same time fits our described scientific model, and maybe even can be explained by the theories conceived by this model.

Knowledge and truth goes hand in hand. Knowledge cannot be considered as knowledge if it at the same time is considered to be untrue. And vice versa. When we state that something is “the truth”, what we are actually saying is that this is knowledge that has been found to match perfectly with our scientific models.

When you start sculpting, you are not sure where this will lead you. But eventually, when you have done a lot of carving, stripped away a lot of dubious claims, and at the end are left with a statue - and if this statue matches the model that you considered to be the blueprint of the truth - then you know that you have reached the correct result, the correct conclusion.

And here we are. When you know, you know. Because the scientifically carved-out model tells you so.

We know that God does not exist

Huh, what? Well, you know what I’m saying - we know that we don’t know, I mean. You understand, right?

Maybe we should take two steps back, and start by agreeing on what it means to “know” something. The answer is not as easy as you would think.

To skip to the conclusion right away, basically what it says is, that we don’t know anything. And in the acknowledgement of that, we simply start writing stuff down. Everything that we believe to be true, we write down as axioms. Then we, armed with all of mankind’s skepticism and ingenuity, try to prove this to be wrong. If we succeed, we delete the axiom, and create a new one, and start the process all over again. If we don’t succeed, and if we can’t find any reasonable arguments that challenges the specific axiom, we decide that we will hereafter call this axiom “true knowledge”.

Armed with our newly acquired list of axioms, we start inferring new knowledge - layer on top of layers - based on this solid foundation, and always systematically questioning any new claims that emerges.

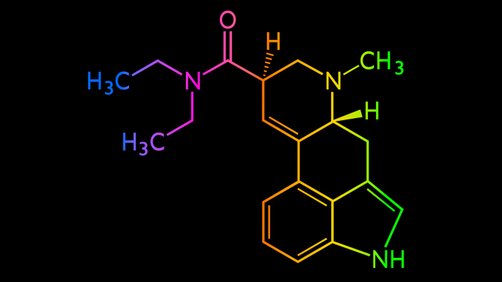

When we follow this methodology, what we are immediately confronted with is, that not only should we question all “truth claims”, but we also need to recognize that the human language is not suited for telling the truth :-) No, let me rephrase. Sentences spoken in the human language can - while being 100% compliant with all grammatical rules - express paradoxes, nonsense and fallacies. There is too much unrestrained plasticity and freedom for artistic expressions (and thank God for that). For science and engineering purposes, we need a language that we can use for communicating knowledge and facts. In this language, the sentences has to communicate their statements in a manner that is inherently explicit, unambiguous and consistent - intrinsically, and in combination with all previously stated “facts”.

Ok, we are getting ahead of ourselves here. The rabbit hole goes much deeper than being just a twist of words. Because we are not ready to define this new scientific language yet. Before we can understand the science and the principles behind this, we need to understand ourselves, and our de facto limitations.

Can you dig it ?

There are many layers to understanding. And if we then on top of that add the need to communicate our knowledge and understanding to another person, it really starts to get complicated.

Everyone has tried to explain something, and been misunderstood. Not because of the language, but because of all the other elements that plays a part in the success of getting the message across. You can probably guess that if an ornithologist starts to explain something about a ‘Bat’ to a long-time fan of Babe Ruth, there could be room for some confusion.

Now imagine explaining something about ‘atoms’. No-one has ever seen an atom, and yet it has become part of our shared vocabulary. But when we can’t see it and can’t draw it, then what are the odds that two people has the same perception of what an atom is ?

Successful communication is based on a shared knowledge base and an unmistakable translation of the statements. The communication makes no sense, if what is being said doesn’t have definite content and meaning.

And as soon as you have understood the message, the next challenge arises. You want to evaluate the truth value of the statement. There is just one thing regarding that. Considering the possibility of something being true is to perform something like a compatibility check - or should I call it a consistency check. If the information in the statement matches everything you already know, and doesn’t contradicts your knowledge about the involved objects, the state they can be in, and what can happen to them, you would consider it to be plausible. But what if someone said to you that “the car is inside the burger”. This sentence is spoken in correct english, but regardless of that, you would immediately know that something is fishy here.

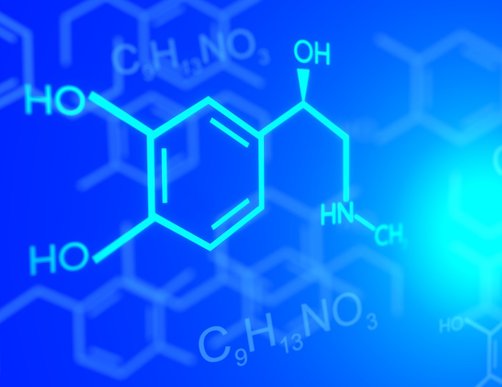

At the end of the day, language and semantics are bound together through a cognitive process in your brain. From the day you were born, your brain has spend 24 hours every day - regardless of whether you were awake or asleep - to build a “model of reality” inside your head. At first, this model was very rudimentary, but while you were growing up, everything you experienced were processed, and helped getting the “model of reality” better and better, more and more precise - one day at a time.

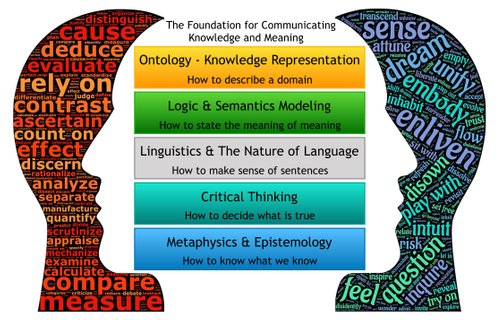

Learn about these 5 layers, and you will learn something about yourself.

In our senses we trust

Our 5 senses. That is what we are relying most of our judgement on. And then luckily also to some extent this huge clump of a jelly walnut located between our ears. And if all our brain could do was to translate and filter the information that comes in through our senses, we would be just another creature on the savanna.

But the Homo Sapiens are to be reckoned with. Since the dawn of Man, our DNA has driven us to question, investigate, seek insight and come up with explanations that can make sense of, and add meaning to what we experience.

This mindset and ability has taken us a long way, down from the trees and into the first settlements of the earliest cities of the world. It has helped us getting food on the table, and protect our families against the hostile environment of the prehistoric world. But simply living, eating, reproducing and dying is not enough for the Sapiens. We are also social beings, and this triggered us to develop a very sophisticated language. And because we are also curious and because we are explorers, we started formulating questions such as: how can it be that .., what if …, can I foresee the next time …, wonder what happens if ….

During the last 10000 years, this has brought us Travel, Trade, Mathematics, Politics, Art and a lot of other good and bad escapades.

Some of the phenomenons we experience, are originating from objects and mechanisms that are too small, or too fast to be caught by the eye. And other manifestations are so extreme and spectacular, that they are breathtaking and almost scary to encounter. In some cases, we can experience such phenomenon, without being able to explain them. And we can give names to them, even through we don’t understand them.

There is a difference between experiencing (hearing and seeing) a thunderstorm, and explaining (understanding) it.

Each time we are confronted with happenings that we haven’t seen before, our current, existing view of the world is being challenged. And if we - after considerable investigations and effort - still have no way of explaining it, something very significant happens. We are left with no option but to modify our world-view. Either we have to let go of previous beliefs, or we might have to introduce new concepts and new metaphysical mechanisms that we can use to explain all the phenomenons we now know of.

Insisting on the need for developing and maintaining a model that can describe the nuts and bolts of how the world functions, has given birth to the many different science disciplines.

But while looking at the world around us, we have also very early on recognized, that we need to look at ourselves, and the role our senses and our mind plays in the process of perceiving and understanding.

Metaphysics and Epistemology

Coming soon.

Creative Thinking

Coming soon.

?

Coming soon.

Linguistics and The Nature of Language

Coming soon.

Taking the Human out of the equation

Coming soon.

Logic and Semantics Modeling

Coming soon.

?

Coming soon.

Ontology - Knowledge Representation

Coming soon.

?

Coming soon.

5 Generic layers as a foundation for all kinds of applications

Coming soon.

@Instagram: istraynot

© Copyright. All Rights Reserved.